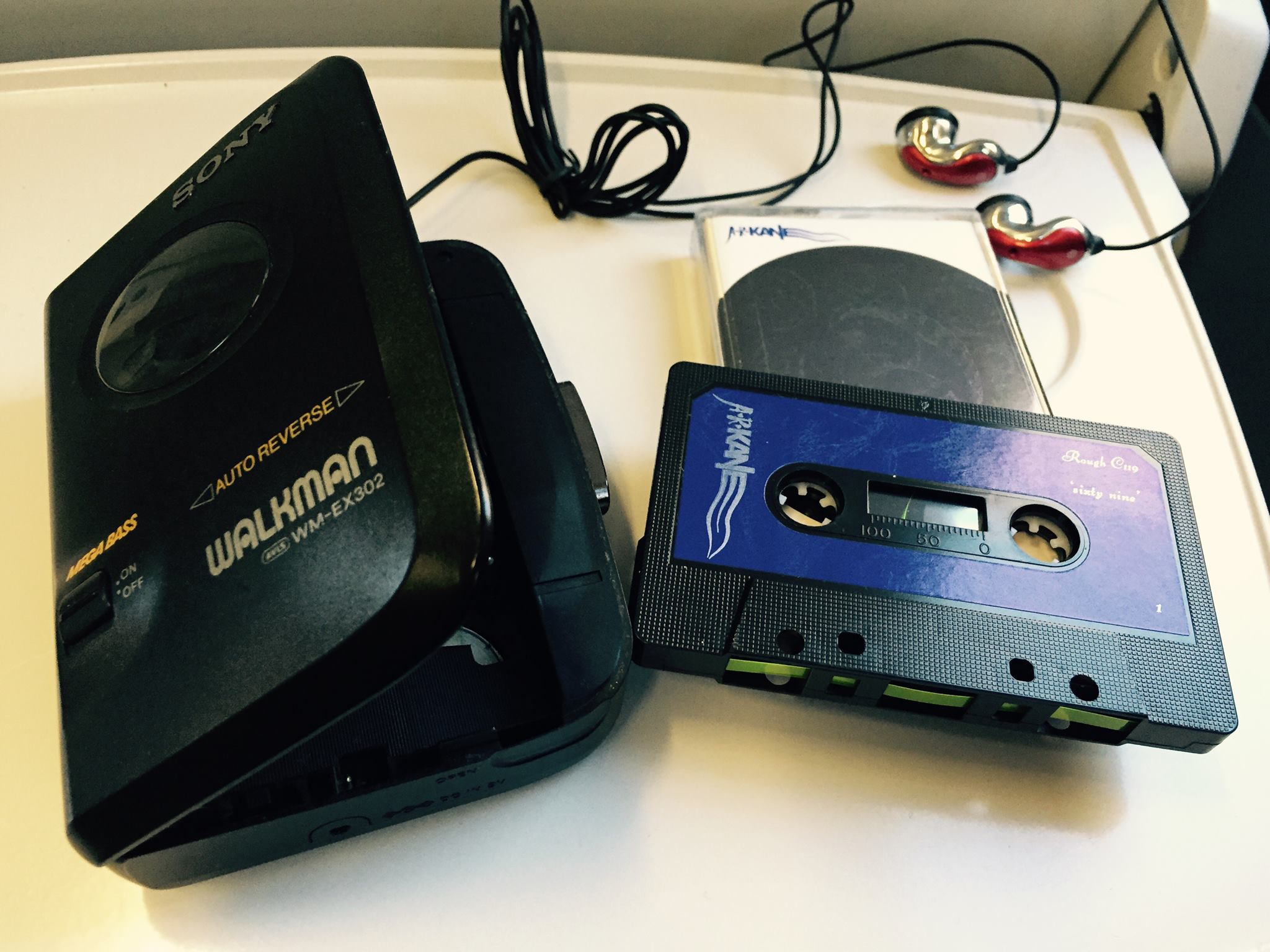

After two decades without news of A.R. Kane, in 2015 they returned under a new group format. The excuse was ideal to interview Rudy Tambala, one of the creators of “69” and “i”, two of the most innovative and avant-garde LPs that the end of the eighties gave us.

Spontaneity is a term so named as difficult to conquer. The electric Miles Davis possibly is one of the best example of all. And I think that something of that spontaneity and freshness is in “69″. Like a dream pop record with the mentality of the jazz-funk rock of Davis, but with dub instead of funk.

RT. Is that a question? No, it is not. Spontaneity was part of our thing, no doubt. And during the live sets this year I began to feel it again. It is confused with randomness, accident, and so on, but like a Pollack, it is not random. It is a feeling, and a desire to serve some truth that cannot be put into words. It requires discipline and sacrifice. It is its own reward. It is hard to maintain, easy to lose, to fall into self-parody. Again, like Pollock. It is, I think, connected to sex – good sex, amazing sex, not everyday sex. It is a type of fucking, holding back, changing rhythm, groove, position …probing- rocking. Coming. Sleeping. Starting again. Oh, to be young again! It’s funny, thinking about this now – I listen to so much new music, and it is beautiful, but it is – like the youth of today – so controlled, so un-spontaneous. It is how things are now- life is dangerous, music is safe.

In your songs more than the love theme, for me, breath the essence of the feeling in the same music and the narcotic voices. Between the idyllic and the perversion, madness or psychosis, like in “Butterfly Collector”, and the destruction that emerges of the same love. Like in the titles of “69”. ‘Spermwhale trip over’, ‘Suicide Kiss’…

RT. Yep, but that isn’t a question, so you’re making me work too hard. Sex, relationships, all that – it is fucked up. Rarely good, nice, harmonious. We used to read books like Ballard’s Crash, and all that stuff. As young men we were experimenting –we were free, to explore not just musically, but in all aspect of our lives – they play off of each other- music, life, life, music – they get mixed up. Musicians – and creative types in general – often have over-inflated libido, to match the super large ego. Sex – biochemically – is involved with the body’s own natural highs – endorphins, oxytocin, and so on. It is a high, a hypnotic. Sex is absurd, without the chemical high – natural of artificial. After sex, food please. After food, sex. Sex has violence, but it is a tender violence, a shared act, complicit, dangerous, essential. But like with sonic experimentation, you can push at the limits, take it to another place. It can become something other, something without love, or affection, or sentimentality. Pain can become virtue, the sado-masochist, virtuous. When we wrote ‘When you’re Sad”, it was originally titled “You push a knife (into my womb)”. The imagery was violent, but the meaning was how within a relationship our security and happiness is fragile, threatened by the mood-swings of our partner. Rough Trade refused to release the single with that title – the PC anarcho-punk collective saw it as violence against women, even though it was about men, about us. Our drummer refused to play on it. No-one listened to our explanation, everyone was so wrapped up in their own heads, their petit bourgeois irrational reactionary modes of behaviour. We said ‘fuck you all’, we decided to use no title, hence ‘When you’re sad’, by default. That was our first single, and our first experience of being outsiders even within the so-called, edgy indie music industry – it set our direction, it was a real eye opener. We were labelled as ‘difficult’ – and we most definitely were – that was an effortless attribute. We had that working class, black macho thing too, a lot of confidence, and a degree of arrogance – youth can be such a bastard. Alex and I had proven ourselves; I had a degree in Biochemistry (only 2 of us went straight from my East End school to university, it was not the done thing – I was one of only 4 or 5 black guys in my college, and that was London University for god sake), and Alex was flying high, the only black guy in a creative role in advertising in London, at Saatchi, driving a flashy car. It sounds very boastful, but that’s how it was – no-one new how to handle us; we knew their worlds, but they never knew ours, and we used that to our benefit, breaking all the rules and fucking with social norms, not just music. It cannot just be the music, it has to be the way one lives – and therein lies the danger, the risk-taking, the fun. It is important to understand the context, because without this, it makes no sense. We created, and recreated, our own culture, our own mythology, on a daily basis. We had no real compass, few peers, more just an instinct. Sex was a centrifugal force. Without sexual experimentation, inquisitiveness, the music would have been jangly pop.

Do you have something in mind before entering in the studio for “69” and “I”? ¿The producers and engineers didn’t want to work with A.R. Kane?

RT. I don’t really understand this question. Sorry. I will try to understand. We had no plans except to make music. With 69 we had to learn how all the gear in our studio fit together, how it ll worked. We created and learned at the same time. Tape machines, compressors, mixing desk, sequencers, samplers, synthesizers, fx boxes, acoustics, mixing, mastering. Because Alex had a job we worked evenings, late into the night, I often walked home at sunrise. With ‘I’ it was different – there were big budgets, big studios, engineers, and all the nonsense that comes with success. We loved it all, and took things as far as we could. Engineers seemed happy to work with us, although we often confronted them and pushed for what we wanted. We never, ever compromised our sound to make things comfortable for everyone. We had to ask some engineers simply to leave, if they could not do as we asked. The way we looked at is, they were being paid to provide a service, and that was the end of the argument. We rarely used producers. I remember so many times either engineers or session players saying “Well I can’t because that is not the way things are done …” How fucking stupid is that? You have to work with the right people, and the space we were in, they were not always easy to find. The A.R.Kane graveyard is filled to the brim. As I said, we were difficult. Never nasty, always very ‘English’ and polite, but unrelenting. To this day, 30 years on, this has not changed, and I’ve seen it all over again whilst trying to pull together the live sound this year. I’m now talking to musicians and producers that I think will get it, it is essential, in service of the music, not the inverse.

For me, “69” it’s a polyphonic sound of oceanic rock, dub production and dream-pop forms. A total new thing that no one else has done. Like the incredible ‘Dizzy’. How was the process of composition and recording of a song so particular like this one?

‘Dizzy’ is too a song with a bipolar feeling. The beauty of the violin and the scream chorus in the background in the same space. I think that is the paradigm of a dream-nightmare becoming something tangible, in the form of a song. How did you perceive this one and the other songs of the record?

RT. It is a bowed double bass, not a violin – played by my friend Billy mcgee – he was the arranger for marc almond, and a talented musician. It was quite methodically experimental – to run the lyric from start to end and end to start too, simultaneously, to be in several places and the same place, to reach a climax only to fall and start again. To be in a very dark and dense place. and to use a simple classical arrangement for stringed instrument. It was like a forest, a haunted forest – cold, dark wood, dead – I was trying to regain, or exorcise, an out-of-body experience I had; I had been experimenting, using a technique for astral projection, whilst lucid dreaming. Enough said about that, eh. I had a very shocking experience, it was as if, whilst out-of-body, something else took up occupation, and it left a residue. Dizzy was how I captured it, to make it easier to live with. To try and remove it. Dreams can be heaven; they can also be hell. Dream pop is not all pretty girls and boys, singing pretty songs over pretty reverbed guitars. I wanted something gothic, Victorian, Bedlam.